To the Editor:

Re “Nixon Looked for ‘Monkey Wrench’ in Vietnam Talks to Help Win Race” (news article, Jan. 3) and “Tricky Dick’s Vietnam Treachery,” by John A. Farrell (Sunday Review, Jan. 1):

When President Lyndon B. Johnson announced his decision not to seek a second term on March 31, 1968, he said he would devote the rest of his presidency trying to secure peace in Vietnam.

Using secret channels to Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese leader, L.B.J. worked relentlessly to persuade Hanoi to begin peace negotiations. He even offered $1 billion to help repair the damage of the war, much as the Marshall Plan did in Germany after World War II. He offered to halt the bombing in return for peace talks.

Finally, in May 1968, the North Vietnamese agreed to meet in Paris with United States and South Vietnamese representatives.

But the South Vietnamese delayed their participation. Newly discovered notes by Bob Haldeman, a Nixon aide, disclose that it was the candidate Richard Nixon himself who, through Anna Chennault, a prominent Republican, encouraged the South Vietnamese to stall until after the 1968 presidential election.

President Johnson suspected but did not know with certainty that Nixon engineered what L.B.J. described as “treason.” Nixon denied it. We now know that was untrue.

In my opinion, public disclosure of Nixon’s actions would have led to a different 1968 election outcome. But L.B.J. did not have the hard evidence needed to prove that Nixon himself had tried to sabotage the peace talks. Now, sadly, we do.

TOM JOHNSON

Atlanta

The writer was an aide to President Johnson, a former publisher of The Los Angeles Times and chairman and chief executive of CNN.

A version of this letter appears in print on January 6, 2017, on Page A18 of the New York edition with the headline: Nixon, L.B.J. and Vietnam Talks: An Insider’s View.

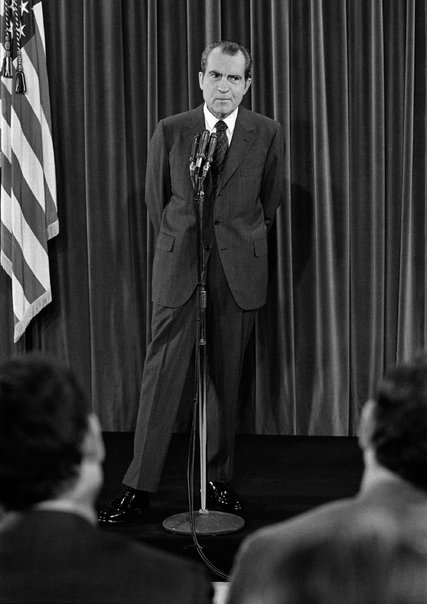

President Richard M. Nixon in 1970. His campaign’s intervention in peace talks in 1968 has captivated historians for years.

Richard M. Nixon told an aide that they should find a way to secretly “monkey wrench” peace talks in Vietnam in the waning days of the 1968 campaign for fear that progress toward ending the war would hurt his chances for the presidency, according to newly discovered notes.

In a telephone conversation with H. R. Haldeman, who would go on to become White House chief of staff, Nixon gave instructions that a friendly intermediary should keep “working on” South Vietnamese leaders to persuade them not to agree to a deal before the election, according to the notes, taken by Mr. Haldeman.

The Nixon campaign’s clandestine effort to thwart President Lyndon B. Johnson’s peace initiative that fall has long been a source of controversy and scholarship. Ample evidence has emerged documenting the involvement of Nixon’s campaign. But Mr. Haldeman’s notes appear to confirm longstanding suspicions that Nixon himself was directly involved, despite his later denials.

“There’s really no doubt this was a step beyond the normal political jockeying, to interfere in an active peace negotiation given the stakes with all the lives,” said John A. Farrell, who discovered the notes at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library for his forthcoming biography, “Richard Nixon: The Life,” to be published in March by Doubleday. “Potentially, this is worse than anything he did in Watergate.”

Mr. Farrell, in an article in The New York Times Sunday Review over the weekend, highlighted the notes by Mr. Haldeman, along with many of Nixon’s fulsome denials of any efforts to thwart the peace process before the election.

His discovery, according to numerous historians who have written books about Nixon and conducted extensive research of his papers, finally provides validation of what had largely been surmise.

While overshadowed by Watergate, the Nixon campaign’s intervention in the peace talks has captivated historians for years. At times resembling a Hollywood thriller, the story involves colorful characters, secret liaisons, bitter rivalries and plenty of lying and spying. Whether it changed the course of history remains open to debate, but at the very least it encapsulated an almost-anything-goes approach that characterized the nation’s politics in that era.

As the Republican candidate in 1968, Nixon was convinced that Johnson, a Democrat who decided not to seek re-election, was deliberately trying to sabotage his campaign with a politically motivated peace effort meant mainly to boost the candidacy of his vice president, Hubert H. Humphrey. His suspicions were understandable, and at least one of Johnson’s aides later acknowledged that they were anxious to make progress before the election to help Mr. Humphrey.

Through much of the campaign, the Nixon team maintained a secret channel to the South Vietnamese through Anna Chennault, widow of Claire Lee Chennault, leader of the Flying Tigers in China during World War II. Mrs. Chennault had become a prominent Republican fund-raiser and Washington hostess.

Nixon met with Mrs. Chennault and the South Vietnamese ambassador earlier in the year to make clear that she was the campaign’s “sole representative” to the Saigon government. But whether he knew what came later has always been uncertain. She was the conduit for urging the South Vietnamese to resist Johnson’s entreaties to join the Paris talks and wait for a better deal under Nixon. At one point, she told the ambassador she had a message from “her boss”: “Hold on, we are gonna win.”

Learning of this through wiretaps and surveillance, Johnson was livid. He ordered more bugs and privately groused that Nixon’s behavior amounted to “treason.” But lacking hard evidence that Nixon was directly involved, Johnson opted not to go public.

The notes Mr. Farrell found come from a phone call on Oct. 22, 1968, as Johnson prepared to order a pause in the bombing to encourage peace talks in Paris. Scribbling down what Nixon was telling him, Mr. Haldeman wrote, “Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN,” or South Vietnam.

A little later, he wrote that Nixon wanted Senator Everett Dirksen, a Republican from Illinois, to call the president and denounce the planned bombing pause. “Any other way to monkey wrench it?” Mr. Haldeman wrote. “Anything RN can do.”

Nixon added later that Spiro T. Agnew, his vice-presidential running mate, should contact Richard Helms, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, and threaten not to keep him on in a new administration if he did not provide more inside information. “Go see Helms,” Mr. Haldeman wrote. “Tell him we want the truth — or he hasn’t got the job.”

After leaving office, Nixon denied knowing about Mrs. Chennault’s messages to the South Vietnamese late in the 1968 campaign, despite proof that she had been in touch with John N. Mitchell, Mr. Nixon’s campaign manager and later attorney general.

Other Nixon scholars called Mr. Farrell’s discovery a breakthrough. Robert Dallek, an author of books on Nixon and Johnson, said the notes “seem to confirm suspicions” of Nixon’s involvement in violation of federal law. Evan Thomas, the author of “Being Nixon,” said Mr. Farrell had “nailed down what has been talked about for a long time.”

Ken Hughes, a researcher at the Miller Center of the University of Virginia, who in 2014 published “Chasing Shadows,” a book about the episode, said Mr. Farrell had found a smoking gun. “This appears to be the missing piece of the puzzle in the Chennault affair,” Mr. Hughes said. The notes “show that Nixon committed a crime to win the presidential election.”

Still, as tantalizing as they are, the notes do not reveal what, if anything, Mr. Haldeman actually did with the instruction, and it is unclear that the South Vietnamese needed to be told to resist joining peace talks that they considered disadvantageous already.

Moreover, it cannot be said definitively whether a peace deal could have been reached without Nixon’s intervention or that it would have helped Mr. Humphrey. William P. Bundy, a foreign affairs adviser to Johnson and John F. Kennedy who was highly critical of Nixon, nonetheless concluded that prospects for the peace deal were slim anyway, so “probably no great chance was lost.”

Luke A. Nichter, a scholar at Texas A&M University and one of the foremost students of the Nixon White House secret tape recordings, said he liked more of Mr. Farrell’s book than not, but disagreed with the conclusions about Mr. Haldeman’s notes. In his view, they do not prove anything new and are too thin to draw larger conclusions.

“Because sabotaging the ’68 peace efforts seems like a Nixon-like thing to do, we are willing to accept a very low bar of evidence on this,” Mr. Nichter said.

An open question is whether Johnson, if he had had proof of Nixon’s personal involvement, would have publicized it before the election.

Tom Johnson, the note taker in White House meetings about this episode, said that the president considered the Nixon campaign’s actions to be treasonous but that no direct link to Nixon was established until Mr. Farrell’s discovery.

“It is my personal view that disclosure of the Nixon-sanctioned actions by Mrs. Chennault would have been so explosive and damaging to the Nixon 1968 campaign that Hubert Humphrey would have been elected president,” said Mr. Johnson, who went on to become the publisher of The Los Angeles Times and later chief executive of CNN.

Mr. Farrell found the notes amid papers that were made public by the Nixon library in July 2007 after the Nixon estate gave them back.

Timothy Naftali, a former director of the Nixon library, said the notes “remove the fig leaf of plausible deniability” of the former president’s involvement. The episode would set the tone for the administration that would follow. “This covert action by the Nixon campaign,” he said, “laid the ground for the skulduggery of his presidency.”

A version of this article appears in print on January 3, 2017, on Page A11 of the New York edition with the headline: Nixon Looked for ‘Monkey Wrench’ In Vietnam Talks to Help Win Race.

Richard M. Nixon always denied it: to David Frost, to historians and to Lyndon B. Johnson, who had the strongest suspicions and the most cause for outrage at his successor’s rumored treachery. To them all, Nixon insisted that he had not sabotaged Johnson’s 1968 peace initiative to bring the war in Vietnam to an early conclusion. “My God. I would never do anything to encourage” South Vietnam “not to come to the table,” Nixon told Johnson, in a conversation captured on the White House taping system.

Now we know Nixon lied. A newfound cache of notes left by H. R. Haldeman, his closest aide, shows that Nixon directed his campaign’s efforts to scuttle the peace talks, which he feared could give his opponent, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, an edge in the 1968 election. On Oct. 22, 1968, he ordered Haldeman to “monkey wrench” the initiative.

The 37th president has been enjoying a bit of a revival recently, as his achievements in foreign policy and the landmark domestic legislation he signed into law draw favorable comparisons to the presidents (and president-elect) that followed. A new, $15 million face-lift at the Nixon presidential library, while not burying the Watergate scandals, spotlights his considerable record of accomplishments.

Haldeman’s notes return us to the dark side. Amid the reappraisals, we must now weigh apparently criminal behavior that, given the human lives at stake and the decade of carnage that followed in Southeast Asia, may be more reprehensible than anything Nixon did in Watergate.

Nixon had entered the fall campaign with a lead over Humphrey, but the gap was closing that October. Henry A. Kissinger, then an outside Republican adviser, had called, alerting Nixon that a deal was in the works: If Johnson would halt all bombing of North Vietnam, the Soviets pledged to have Hanoi engage in constructive talks to end a war that had already claimed 30,000 American lives.

Anna Chennault, 1969.CreditIra Gay Sealy/The Denver Post, via Getty Images

But Nixon had a pipeline to Saigon, where the South Vietnamese president, Nguyen Van Thieu, feared that Johnson would sell him out. If Thieu would stall the talks, Nixon could portray Johnson’s actions as a cheap political trick. The conduit was Anna Chennault, a Republican doyenne and Nixon fund-raiser, and a member of the pro-nationalist China lobby, with connections across Asia.

“! Keep Anna Chennault working on” South Vietnam, Haldeman scrawled, recording Nixon’s orders. “Any other way to monkey wrench it? Anything RN can do.”

Nixon told Haldeman to have Rose Mary Woods, the candidate’s personal secretary, contact another nationalist Chinese figure — the businessman Louis Kung — and have him press Thieu as well. “Tell him hold firm,” Nixon said.

Nixon also sought help from Chiang Kai-shek, the president of Taiwan. And he ordered Haldeman to have his vice-presidential candidate, Spiro T. Agnew, threaten the C.I.A. director, Richard Helms. Helms’s hopes of keeping his job under Nixon depended on his pliancy, Agnew was to say. “Tell him we want the truth — or he hasn’t got the job,” Nixon said.

Throughout his life, Nixon feared disclosure of this skulduggery. “I did nothing to undercut them,” he told Frost in their 1977 interviews. “As far as Madame Chennault or any number of other people,” he added, “I did not authorize them and I had no knowledge of any contact with the South Vietnamese at that point, urging them not to.” Even after Watergate, he made it a point of character. “I couldn’t have done that in conscience.”

Nixon had cause to lie. His actions appear to violate federal law, which prohibits private citizens from trying to “defeat the measures of the United States.” His lawyers fought throughout Nixon’s life to keep the records of the 1968 campaign private. The broad outline of “the Chennault affair” would dribble out over the years. But the lack of evidence of Nixon’s direct involvement gave pause to historians and afforded his loyalists a defense.

Time has yielded Nixon’s secrets. Haldeman’s notes were opened quietly at the presidential library in 2007, where I came upon them in my research for a biography of the former president. They contain other gems, like Haldeman’s notations of a promise, made by Nixon to Southern Republicans, that he would retreat on civil rights and “lay off pro-Negro crap” if elected president. There are notes from Nixon’s 1962 California gubernatorial campaign, in which he and his aides discuss the need to wiretap political foes.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that, absent Nixon, talks would have proceeded, let alone ended the war. But Johnson and his advisers, at least, believed in their mission and its prospects for success.

When Johnson got word of Nixon’s meddling, he ordered the F.B.I. to track Chennault’s movements. She “contacted Vietnam Ambassador Bui Diem,” one report from the surveillance noted, “and advised him that she had received a message from her boss … to give personally to the ambassador. She said the message was … ‘Hold on. We are gonna win. … Please tell your boss to hold on.’ ”

In a conversation with the Republican senator Everett Dirksen, the minority leader, Johnson lashed out at Nixon. “I’m reading their hand, Everett,” Johnson told his old friend. “This is treason.”

“I know,” Dirksen said mournfully.

Johnson’s closest aides urged him to unmask Nixon’s actions. But on a Nov. 4 conference call, they concluded that they could not go public because, among other factors, they lacked the “absolute proof,” as Defense Secretary Clark Clifford put it, of Nixon’s direct involvement.

Nixon was elected president the next day.

John A. Farrell is the author of the forthcoming “Richard Nixon: The Life.”

A version of this article appears in print on Jan. 1, 2017, on Page SR9 of the New York edition with the headline: Tricky Dick’s Vietnam Treachery

In the early spring of 1967, I was in the middle of a heated 2 a.m. hallway discussion with fellow students at Yale about the Vietnam War. I was from a small town in Oregon, and I had already joined the Marine Corps Reserve. My friends were mostly from East Coast prep schools. One said that Lyndon B. Johnson was lying to us about the war. I blurted out, “But … but an American president wouldn’t lie to Americans!” They all burst out laughing.

When I told that story to my children, they all burst out laughing, too. Of course presidents lie. All politicians lie. God, Dad, what planet are you from?

Before the Vietnam War, most Americans were like me. After the Vietnam War, most Americans are like my children.

America didn’t just lose the war, and the lives of 58,000 young men and women; Vietnam changed us as a country. In many ways, for the worse: It made us cynical and distrustful of our institutions, especially of government. For many people, it eroded the notion, once nearly universal, that part of being an American was serving your country.

1968 Election : Nixon’s Treachery

Editor’s Note: One of the nagging questions connected to the war in Viet Nam concerns the presidential election of 1968 in the U.S.: Lyndon Johnson abdicated in April, ceding the nomination likely to his VP, Hubert Humphrey, if he could defeat his 2 main challengers: Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy. As fate would interneve: Kennedy defeated McCarthy only to be assassinated right after his primary victory in California in June.

LBJ proposed a peace talk in Paris to resolve issues related to the war, and ultimately reach a peace. President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu of the Republic of Việt Nam proved reluctant to join the talks. Did he hope for a better outcome with Nixon in the White House? Did he hold out to indirectly assist Nixon? Did Nixon reach out to Thieu with such promise?

A month ago, the New York Times clarified the issue with some new data. TRỒNG NGƯỜI reprints below a few relevant pieces for our readers who might have missed them, or who may want to save them for future reference.

LTS.: Năm 1968 là thời điểm chấn động nhất sau thế chiến thứ 2. Khởi đầu là cuộc Tổng tấn công vào những ngày đầu năm Mậu Thân; rồi các diễn biến chính trị trên toàn cầu: sinh viên, công nhân biểu tình ở Pháp, ở Nhật, v.v… Riêng tại Mỹ, trận Mậu Thân làm nhụt chí tổng thống Lyndon Johnson, dẫn đến việc ông từ nhiệm không tranh cử nhiệm kỳ 2; Sự kiện này dẫn đến một mùa tranh cử náo động nhất ở Mỹ kể từ ngày lập quốc, với ứng viên thành công sớm là TNS Eugene McCarthy, rồi đến TNS Robert Kennedy nhưng lại bị ám sát trong đêm thắng cử sơ bộ tại bang California; để còn lại 2 ứng viên chính vào tháng 11/68: Hubert Humphrey của Đảng Dân Chủ và Richard Nixon của Đảng Cộng Hòa. Một sự kiện lịch sử nữa ở Mỹ là vụ ám sát mục sư Martin Luther King, Jr. vào tháng tư.

Một câu hỏi mà giới trí thức Việt cũng như Mỹ đều thắc mắc là trong cuộc bầu cử tổng thống năm 1968, liệu ứng viên Nixon có “đi đêm” với TT Nguyễn Văn Thiệu của miền Nam và là đồng minh của Mỹ, để VNCH không tham gia cuộc đàm phán tại Paris do TT Johnson đề xuất, và như vậy giúp ông Nixon phần nào không? Kết quả cuộc bầu cử năm đó là Richard Nixon thắng và kéo dài cuộc chiến đến 1973, sau khi đã bán đứng cả VN lẫn Đài Loan cho Mao.

Tháng trước, truyền thông bên Mỹ mới có chứng cứ chắc chắn để trả lời thắc mắc trên. TRỒNG NGƯỜI đăng lại dưới đây vài bài liên quan để rộng đường dư luận cũng như giúp các bạn sinh viên, các nhà nghiên cứu có thêm tài liệu cập nhật và chính xác.

GS ngôn ngữ Nguyễn Đức Dân (Trường ĐH Khoa học Xã hội và Nhân văn, TP.HCM): Không nêu chức danh "giáo sư chung chung":

Tôi hoàn toàn ủng hộ việc các trường ĐH tự xác định chức danh GS, PGS cho trường mình vì nhiệm vụ khoa học với điều kiện các cá nhân sau khi được xác định phải có ý thức nêu trên danh thiếp và giới thiệu rõ ràng đây là là GS, PGS của trường A hoặc của trường B chứ không được nêu chức danh này một cách chung chung, gây nhầm lẫn.

Sau khi có thông tin Trường ĐH Tôn Đức Thắng đang triển khai thực hiện việc phong giáo sư (GS), phó giáo sư (PGS) cho cán bộ, giảng viên, nhà khoa học trong và ngoài nhà trường, ông Bùi Mạnh Nhị, Chánh Văn phòng Hội đồng Chức danh Giáo sư Nhà nước khẳng định việc làm này không có tính pháp lý.

Trường ĐH Tôn Đức Thắng đang triển khai thực hiện việc phong giáo sư (GS), phó giáo sư (PGS) cho cán bộ, giảng viên, nhà khoa học trong và ngoài nhà trường.

TS Lê Văn Út, Trưởng phòng Quản lý phát triển KH&CN Trường ĐH Tôn Đức Thắng, cho biết việc này được triển khai trên cơ sở tìm hiểu, vận động cách thức các trường ĐH uy tín trên thế giới vào tình hình thực tế của trường.

Tại buổi gặp, ông Vũ An Ninh, Trưởng phòng tổ chức hành chính nhà trường, cho biết việc bổ nhiệm chức danh GS, PGS của nhà trường không phải là phong học hàm như quy định của Hội đồng chức danh GS Nhà nước. Đây chỉ là việc bổ nhiệm chức vụ chuyên môn. Việc Nhà nước phong học hàm thì trường nào cũng chấp nhận. Riêng GS, PGS do trường bổ nhiệm chỉ gói gọn với đối tượng trong trường, giới hạn thời gian làm việc với trường. Đây không phải là chức danh, học hàm được hưởng ưu đãi theo quy định của Nhà nước. Ngoài việc hưởng hệ số lương theo vị trí công việc như quy định, đội ngũ này còn được trường trả mức phụ cấp riêng. Trường khác có công nhận các chức danh này hay không thì tùy các trường.

Các chuyên gia đã có nhiều góc nhìn khác nhau trước sự kiện ĐH Tôn Đức Thắng bổ nhiệm PGS, GS.